3.8 Develop an informed understanding of literature and/or language using critical texts.

Suggested texts for study and optional hypotheses:

“In times of suspicion, truth is often the first casualty.”

“People believe the truth that most suits their view of the world.”

“The action of the play is primarily driven by lies.”

“Abigail’s character is best understood as a product of her environment.”

For Martin, from our whiteboard at school:

The complex issues embedded in modern-day ‘fake news’ are applicable to the problems represented in THE CRUCIBLE

The action of the play is driven by lies.

The characters consistently use lies and deception to protect their reputations.

Abigail/John Proctor does not deserve her/his role as a villain/hero.

Power is used as a weapon in The Crucible.

Orwell’s criticism of the government was so prescient because he mined the depths of universal human nature.

The Crucible by Arthur Miller https://archive.org/stream/TheCrucibleFullText/The+Crucible+full+text_djvu.txt

Article about Fake News: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20170301-lies-propaganda-and-fake-news-a-grand-challenge-of-our-age

Article about political leaning dictating the understanding of the Covid19 crisis: https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2020/3/31/21199271/coronavirus-in-us-trump-republicans-democrats-survey-epistemic-crisis

Article about the moral questions raised by the pandemic. Is it okay to sunbathe? Links to questions raised by The Crucible in terms of “Who is right?” “Why are they right?”

Extra – for 3.7 preparation: Othello by William Shakespeare, or Truman Show

Steps for critical analysis:

1. READ the text(s).

2. IDEAS: Understand meaning. When you read it, what did you think it was saying? What ideas did you get? What messages do you think the text was trying to help you understand?

3. PURPOSE & AUDIENCE: Identify who the writer was trying to reach and why. Who would like this text? Who would hate it? Why? What purpose did bringing up those ideas, in that way, have? Did it make you (the audience) question, believe, understand or imagine something new? Did it make you reflect on your own life and your own experiences? Or did it invite you to go outside of yourself to better understand the experiences of others in society? Why might this purpose be important? Was the text asking you to take action? Calm down? Laugh? Cry?

4. QUESTION THE ANALYSIS: Now you know what the text was saying, why it was saying it and who it was trying to say it to, you have completed an ‘analysis’ of the text. To critically analyse is to then ANALYSE your ANALYSIS. In other words, question any and all of the assumptions your analysis may contain. For example: So what if the text was saying that? So what if the writer wanted us to understand that? Who cares? Whose shoes would I need to be in to see it differently? What’s outside the box? What’s another way of looking at it? How is the way I understand it today, different from how it might have been understood at other times or from other viewpoints?

Critical analysis requires an awareness that a text can be interpreted in many different ways. Forensically, a literature study is just as scientific as any other discipline. The raw materials of a text must be tested and are only open to interpretation based on the discovery of evidence, compelling argument and the weighing up of plausibilities to reach a judgment or conclusion.

This dynamism of new ways of reading a text exists because while the text remains the same – the audience constantly changes. We recognise a character’s feelings from hundreds of years ago because people and our human tendencies are universal over time and space. Things get exciting when this is coupled with the fact that society, our rules, our traditions, our technologies, our environments, and our beliefs about ourselves and others are always in flux and changing. These two factors: Our innate humanity vs the constantly changing perception of “what is humanity?” is the fascinating engine that drives any investigation into any creation of literature.

When you embark on a critical analysis keep in mind: So what? Who cares? Whose shoes? What’s outside the box?

You’ll need some critical texts from experts who have already taken a ‘critical look’ at what you are studying and shared their own discoveries, evidence, arguments, and conclusions.

Your job is to look at the text, choose a hypothesis, look at two or more relevant critical texts, weigh up the evidence, make your own argument and then draw your own conclusions regarding your hypothesis.

It’s an oldie but a goodie. Look here for Harold Bloom’s collection of critical texts about The Crucible.

From Arthur Miller himself: “Why I wrote The Crucible.”

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/10/21/why-i-wrote-the-crucible

Arthur Miller’s The Crucible: Fact & Fiction (or Picky, Picky, Picky…)

Author: Margo Burns

Name of Page: Arthur Miller’s The Crucible: Fact & Fiction (or Picky, Picky, Picky…)

Name of institution/organization publishing the site: This site has no institutional affiliation, although you may want to include the name of the entire website,17th Century Colonial New England, depending on the format you use.

Date of Posting/Revision: Sep. 25, 2018

Website address: http://www.17thc.us/docs/fact-fiction.shtml

Date Retrieved/Viewed: Jan. 6, 2020

Arthur Miller’s The Crucible:Fact & Fiction

(or Picky, Picky, Picky…) by Margo Burns Revised: 10/18/12

I’ve been working with the materials of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692 for so long as an academic historian, it’s not surprising when people ask me if I’ve seen the play or film The Crucible, and what I think of it. Miller created works of art, inspired by actual events, for his own artistic/political intentions. First produced on Broadway on January 22, 1953, the play was partly a response to the panic caused by irrational fear of Communism during the Cold War which resulted in the hearings by the House Committee on Unamerican Activities.1 In Miller’s play and screenplay, however, it is a lovelorn teenager, spurned by the married man she loves, who fans a whole community into a blood-lust frenzy in revenge. This is simply not history. The real story is far more complex, dramatic, and interesting – and well worth exploring. Miller himself had some things to say about the relationship between his play and the actual historical event that are worth considering. In the Saturday Review in 1953, Henry Hewes quotes Miller as stating, “A playwright has no debt of literalness to history. Right now I couldn’t tell you which details were taken from the records verbatim and which were invented.” I, on the other hand, can tell you, and that is the purpose of this essay.

Whether this activity is worthwhile or not really depends on what one wants from the play or movie. I find that many people come across this unusual episode in American history through Miller’s story, and if they want to start learning what “really” happened in 1692, they have a hard time distinguishing historical fact from literary fiction because Miller’s play and characters are so vivid, and he used the names of real people who participated in the historical episode for his characters. Miller wrote a “Note on the Historical Accuracy of this Play” at the beginning of the Viking Critical Library edition:

This play is not history in the sense in which the word is used by the academic historian. Dramatic purposes have sometimes required many characters to be fused into one; the number of girls involved in the ‘crying out’ has been reduced; Abigail’s age has been raised; while there were several judges of almost equal authority, I have symbolized them all in Hathorne and Danforth. However, I believe that the reader will discover here the essential nature of one of the strangest and most awful chapters in human history. The fate of each character is exactly that of his historical model, and there is no one in the drama who did not play a similar – and in some cases exactly the same – role in history.

As for the characters of the persons, little is known about most of them except what may be surmised from a few letters, the trial record, certain broadsides written at the time, and references to their conduct in sources of varying reliability. They may therefore be taken as creations of my own, drawn to the best of my ability in conformity with their known behavior, except as indicated in the commentary I have written for this text. (p. 2)

Miller clings to simultaneous claims of creative license and exactitude about the behavior and fate of the real people whose names he used for his characters. This is problematic for anyone who is beginning to take an interest in the historical episode, based on his powerful play.2

In Miller’s autobiography, Timebends: A Life, originally published in 1987, Miller recounts another impression he had during his research:

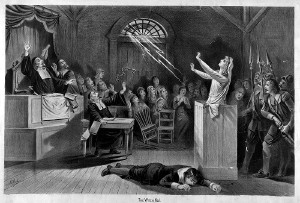

One day, after several hours of reading at the Historical Society […] I got up to leave and that was when I noticed hanging on a wall several framed etchings of the witchcraft trials, apparently made by an artist who must have witnessed them. In one of them, a shaft of sepulchral light shoots down from a window high up in a vaulted room, falling upon the head of a judge whose face is blanched white, his long white beard hanging to his waist, arms raised in defensive horror as beneath him the covey of afflicted girls screams and claws at invisible tormentors. Dark and almost indistinguishable figures huddle on the periphery of the picture, but a few men can be made out, bearded like the judge, and shrinking back in pious outrage. Suddenly it became my memory of the dancing men in the synagogue on 114th Street as I had glimpsed them between my shielding fingers, the same chaos of bodily motion – in this picture, adults fleeing the sight of a supernatural event; in my memory, a happier but no less eerie circumstance – both scenes frighteningly attached to the long reins of God. I knew instantly what the connection was: the moral intensity of the Jews and the clan’s defensiveness against pollution from outside the ranks. Yes, I understood Salem in that flash; it was suddenly my own inheritance. I might not yet be able to work a play’s shape out of this roiling mass of stuff, but it belonged to me now, and I felt I could begin circling around the space where a structure of my own could conceivably rise. [p. 338]3

There are no extant drawings by witnesses to the events in 1692. My best guess is that what Miller may have seen was a lithograph – popular framed wall art in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – from a series produced in 1892 by George H. Walker & Co., drawn by Joseph E. Baker (1837-1914) [See image to the right to compare with Miller’s description.]. Although it is fine for artist to be inspired by whatever stimulates their creative sensibilities, Miller’s descriptions of his own research, however credible they may come across and however vivid an imprint they may have left on him, are riddled with inaccuracies, and memories Miller claims to have had of the primary sources, are seriously flawed.

There are no extant drawings by witnesses to the events in 1692. My best guess is that what Miller may have seen was a lithograph – popular framed wall art in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – from a series produced in 1892 by George H. Walker & Co., drawn by Joseph E. Baker (1837-1914) [See image to the right to compare with Miller’s description.]. Although it is fine for artist to be inspired by whatever stimulates their creative sensibilities, Miller’s descriptions of his own research, however credible they may come across and however vivid an imprint they may have left on him, are riddled with inaccuracies, and memories Miller claims to have had of the primary sources, are seriously flawed.

When the movie was released 1996, Miller published an article in the New Yorker, discussing “Why I Wrote The Crucible”, in which he describes, over four decades after writing the play, what he remembered of his process with the material. He began by stating that he had read Salem Witchcraft: “[I]t was not until I read a book published in 1867 – a two-volume, thousand-page study by Charles W. Upham, who was then the mayor of Salem – that I knew I had to write about the period.” It was in Upham’s work that Miller encountered the description of a single gesture that inspired him:

It was from a report written by the Reverend Samuel Parris, who was one of the chief instigators of the witch-hunt. “During the examination of Elizabeth Procter, Abigail Williams and Ann Putnam” – the two were ‘afflicted’ teen-age accusers, and Abigail was Parris’s niece – “both made offer to strike at said Procter; but when Abigail’s hand came near, it opened, whereas it was made up into a fist before, and came down exceeding lightly as it drew near to said Procter, and at length, with open and extended fingers, touched Procter’s hood very lightly. Immediately Abigail cried out her fingers, her fingers, her fingers burned….” In this remarkably observed gesture of a troubled young girl, I believed, a play became possible.

This is terrific stuff for a fertile, creative mind (see Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt, No. 49, p. 174 for a transcription of the full primary source), and immediately Miller veered away from the historical record, imagining the backstory of this gesture: “Elizabeth Proctor had been the orphaned Abigail’s mistress, and they had lived together in the same small house until Elizabeth fired the girl. By this time, I was sure, John Proctor had bedded Abigail, who had to be dismissed most likely to appease Elizabeth.” That’s fine fiction, as long as readers know that this was his creative mind at work not what really happened, but even in discussing his own work, Miller is often unable to tell what was historically true and what he had made up. In the introduction to his Collected Plays published in 1957 (republished in the Viking Critical Library edition, p. 164), Miller claimed that the story of Abigail Williams as a servant in the Procter house was historically accurate:

I doubt I should ever have tempted agony by actually writing a play on the subject had I not come upon a single fact. It was that Abigail Williams, the prime mover of the Salem hysteria, so far as the hysterical children were concerned, had a short time earlier been the house servant of the Proctors and now was crying out Elizabeth Proctor as a witch; but more – it was clear from the record that with entirely uncharacteristic fastidiousness she was refusing to include John Proctor, Elizabeth’s husband, in her accusations despite the urgings of the prosecutors.

This is also not historically accurate: the real Abigail Williams cried out against John Procter on April 4, on the same day Elizabeth Procter was formally accused, although he was not included on the arrest warrant issued on April 8. (See RSWH, Nos. 39, 46, 47 & 61). Miller continued to claim that it was a fact. “It was the fact that Abigail, their former servant, was their accuser, and her apparent desire to convict Elizabeth and save John, that made the play conceivable for me.” (Viking Critical Library edition, p. 165) What Miller had to say about the line between his play and historical accuracy is as unreliable as the play itself is as history.

Another example of this fictionalization of this research can be found in Miller’s article “Are You Now Or Were You Ever?”, published in The Guardian/The Observer (on line), on Saturday, June 17, 2000. He wrote, “I can’t recall if it was the provincial governor’s nephew or son who, with a college friend, came from Boston to watch the strange proceedings. Both boys burst out laughing at some absurd testimony: they were promptly jailed, and faced possible hanging.” As delightfully ironic as this sounds, again, it is simply fabricated, although whether by Miller himself or from some secondary source he may have read – he states in this article that he had read Marion Starkey’s book,The Devil in Massachusetts (1949), for instance – but there is simply nothing even remotely like this mentioned in the primary sources.

Miller is, of course, not alone in his misconceptions about the history of this episode. He was using it to make sense of his own life and times. Popular understandings include many general inaccuracies – for instance, that the witches were burned to death. People condemned as witches in New England were not burned, but hanged, and in the aftermath of the events in Salem, it was generally agreed that none of them had actually been witches at all. Some modern versions also cast the story as having to do with intolerance of difference – a theme that was in the words of Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel at the dedication of the Tercentenary Memorial in Salem in August 1992, for instance – that the accused were people on the fringes that the community tacitly approved of casting out. In fact, most of the people who were accused, convicted, and executed by the court in Salem were remarkable by their very adherence to community norms, many were even fully covenanted members of the church. Such impressions that vary from the historical facts are more likely to come from pressing concerns of the time of the writer.

Another current misconception about the events had its beginning in 1976, when Linnda P. Caporael, then a graduate student, published an article in Science magazine positing that the afflicted had suffered from hallucinations from eating moldy rye wheat – ergot poisoning. The story was picked up and published on the front page of the New York Times on March 31, 1976, in the article “Salem Witch Hunts in 1692 Linked to LSD-Like Agent”. The use and abuse of LSD was a major public concern at the time. The theory was refuted, point by point, by Nickolas P. Spanos and Jack Gottlieb seven months later in the very magazine Caporael had published her original article, demonstrating how Caporael’s data was cherry-picked to support her conclusion. For instance, the kind of ergotism that produces hallucinations has other symptoms – gangrene fingers and digestive-tract distress – which would likely have been reported in 1692, but were not. Nevertheless the life of this theory continues in the popular imagination as a viable explanation of the events. It was later backed up by Mary Matossian in 1982 in an article in American Scientist, “Ergot and the Salem witchcraft affair” (also covered by the New York Times, 8/29/1982), and in her 1989 book Poisons of the Past: Molds, Epidemics and History. Caporael herself re-appeared in 2001 on the subject, in a PBS special in the series Secrets of the Dead II: “Witches Curse”, repeating her claims, unrefuted. Another biological theory, by Laurie Winn Carlson, published in 1999, suggested that the afflicted suffered from encephalitis lethargica, but this one also fails to hold up under the scrutiny of medical and Salem scholars alike. Additionally, even if these biological explanations could be the root of the accusers’ “visions”, they still do not go far to explain the credulity and legal response of the public and authorities. They do reflect a current perception that unacknowledged toxins in our daily environment can explain many medical issues.

Lastly, Rev. Parris’ slave woman, Tituba, is persistently portrayed as having been of Black African descent or of mixed racial heritage, despite always being referred to in the primary sources as “an Indian woman”. This presentation of Tituba, known to have been a slave from Barbadoes, began in the Civil War era, when most slaves from Barbadoes were, in fact, of Black African heritage. Had the real Tituba nearly two centuries earlier actually been African or Black or mulatto, she would have been so described. Contemporary descriptions of her also refer to her as a “Spanish Indian”, placing her pre-Barbadoes origins somewhere in the Carolinas, Georgia or Florida. Historian Elaine Breslaw details how we know that Tituba was Amerindian, probably South American Arawak. (See my supplemental notes about Tituba.)

Returning to Miller’s tellings of the tale, I am always distracted by the wide variety of minor historical inaccuracies when I am exposed to his play or movie. Call me picky, but I’m not a dolt: I know about artistic license and Miller’s freedom to use the material any way he choose to, so please don’t bother lecturing me about it. This page is part of a site about the history of 17th Century Colonial New England, not about literature, theater, or Arthur Miller, even though you may have landed smack dab in the middle of the site thanks to a search engine hit for information about Miller.

Reasons why I began providing this list include, 1) actors contact me about making their portrayals of characters in the play “more accurate” – when that is impossible without drastically altering Miller’s work because the characters in his play are simply not the real people who lived, even though they may share names and basic fates, 2) people who are watching the stage production or movie and who are inspired to learn more about the historical event, and 3) students are given assignments in their English classes to find out more about what really happened (American high school juniors in honors and AP classes seem to be the most frequent visitors). I can be an ornery cuss when it comes to being asked the same English class homework questions that I’ve already said I don’t care to answer because I am an historian, so before you even think of writing to ask me a question about the play, please read through my list of frequently-asked questions where I will give you what answers I have to offer to the most questions I am most commonly asked – be prepared: they may not be the answers you want.

Here’s my list of some of the historical inaccuracies in the play/screenplay:

-

Abigail tells Betty, “Your Mama’s dead and buried!”, (Screenplay, Scene 21; play, Act 1, Scene 1). Betty Parris’ mother was not dead and was very much alive in 1692. Elizabeth (Eldridge) Parris died four years after the witchcraft trials, on July 14, 1696, at the age of 48. Her gravestone is located in the Wadsworth Cemetery on Summer Street in Danvers, MA:http://gravematter.smugmug.com/gallery/903002#41044279_2RnRT

-

Soon after the legal proceedings began, Betty was shuttled off to live in Salem Town with Stephen Sewall’s family. Stephen was the clerk of the Court, brother of Judge Samuel Sewall.

-

The Parris family also included two other children — an older brother, Thomas (b. 1681), and a younger sister, Susannah (b. 1687) — not just Betty and her relative Abigail, who was probably born around 1681.

-

Abigail Williams is often called Rev. Parris’ “niece” but in fact there is no genealogical evidence to prove their familial relationship. She is sometimes in the original texts referred to as his “kinfolk” however.

-

Miller admits in the introduction to the play that he boosted Abigail Williams’ age to 17 even though the real girl was only 11, but he never mentions that John Proctor was 60 and Elizabeth, 41, was his third wife. Proctor was not a farmer but a tavern keeper. Living with them was their daughter aged 15, their son who was 17, and John’s 33-year-old son from his first marriage. Everyone in the family was eventually accused of witchcraft. Elizabeth Proctor was indeed pregnant, during the trial, and did have a temporary stay of execution after convicted, which ultimately spared her life because it extended past the end of the period that the executions were taking place.

-

There never was any wild dancing rite in the woods led by Tituba, and certainly Rev. Parris never stumbled upon them. Some of the local girls had attempted to divine the occupations of their future husbands with an egg in a glass — crystal-ball style. Tituba and her husband, John Indian (absent in Miller’s telling), were asked by a neighbor, Mary Sibley, to bake a special “witch cake,” — made of rye and the girls’ urine, fed to a dog — European white magic to ascertain who the witch was who was afflicting the girls. Supplemental Notes

-

The first two girls to become afflicted were Betty Parris and Abigail Williams, and they had violent, physical fits, not a sleep that they could not wake from.

-

The Putnams’ daughter was not named Ruth, but Ann, like her mother, probably changed by Miller so the audience wouldn’t confuse the mother and the daughter. In reality, the mother was referred to as “Ann Putnam Senior” and the daughter as “Ann Putnam Junior.”

-

Ann/Ruth was not the only Putnam child out of eight to survive infancy. In 1692, the Putnams had six living children, Ann being the eldest, down to 1-year-old Timothy. Ann Putnam Sr. was pregnant during most of 1692. Ann Sr. and her sister, however did lose a fair number of infants, though certainly not all, and by comparison, the Nurse family lost remarkably few for the time.

-

Rev. Parris claims to Giles Corey that he is a “graduate of Harvard” — he did not in fact graduate from Harvard, although he had attended for a while and dropped out.

-

The judges in The Crucible are Thomas Danforth, and John Hathorne in the play, with Samuel Sewall added for the screenplay. The full panel of magistrates for the special Court of Oyer and Terminer were in fact named by the new charter, which arrived in Massachusetts on May 14, 1692 were William Stoughton, John Richards, Nathaniel Saltonstall, Wait Winthrop, Bartholomew Gedney, Samuel Sewall, John Hathorne, Jonathan Corwin and Peter Sergeant. Five of these had to be present to form a presiding bench, and at least one of those five had to be Stoughton, Richards, or Gedney. Thomas Danforth, as Deputy Governor and a member of the Governor’s Council, joined the magistrates on one occasion as the presiding magistrate in Salem for the preliminary examinations in mid-April of Sarah Cloyce, Elizabeth Procter and John Procter, but once the new charter arrived with Gov. Phips in May, William Stoughton became the Lieutenant Governor and Chief Magistrate.

-

The events portrayed here were the examinations of the accused in Salem Village from March to April, in the context of a special court of “Oyer and Terminer.” These were not the actual trials, per se, which began later, in June 1692. The procedure was basically this: someone would bring a complaint to the authorities, and the authorities would decide if there was enough reason to send the sheriff or other law enforcement officer to arrest them. While this was happening, depositions — statements people made on paper outside of court — were taken and evidence gathered, typically against the accused. After evidence or charges were presented, and depositions sworn to before the court, the grand jury would decide whether to indict the person, and if so, on what charges. If indicted, the person’s case would be heard by a petit jury, basically to “trial”, something like we know it only much faster, to decide guilt or innocence. Guilt in a case of witchcraft in 1692 came with an automatic sentence of death by hanging, as per English law.

-

Saltonstall was one of the original magistrates, but quit early on because of the reservations portrayed as attributed to Sewall’s character in the play. Of the magistrates, only Sewall ever expressed public regret for his actions, asking in 1696 to have his minister, Rev. Samuel Willard, read a statement from the pulpit of this church to the congregation, accepting his share of the blame for the trials.

-

Rebecca Nurse was hanged on July 19, John Proctor on August 19, and Martha Corey on September 22 — not all on the same day on the same gallows. And the only person executed who recited the Lord’s Prayer on the gallows was Rev. George Burroughs — which caused quite a stir since it was generally believed at the time that a witch could not say the Lord’s Prayer without making a mistake. They also would not have been hanged while praying, since the condemned were always allowed their last words and prayers.

-

Reverend Hale would not have signed any “death warrants,” as he claims to have signed 17 in the play. That was not for the clergy to do. Both existing death warrants are signed by William Stoughton.

-

The elderly George Jacobs was not accused of sending his spirit in through the window to lie on the Putnam’s daughter – in fact, it was usually quite the opposite case: women such as Bridget Bishop were accused of sending their spirits into men’s bedrooms to lie on them. In that period, women were perceived as the lusty, sexual creatures whose allure men must guard against!

-

The real John Procter (vs. the fictional John Proctor in the play) maintained his innocence throughout, however another accused man – whose wife was also accused – did confess and recant and was hanged: Samuel Wardwell of Andover. When pressed to confirm the text of his confession, Wardwell refused, stating, “the above written confession was taken from his mouth, and that he had said it, but he said he belied himself.” He also said, “He knew he should die for it, whether he owned it or not.” (See Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt, No.538, p. 577)

-

The hysteria did not die out “as more and more people refused to save themselves by giving false confessions,” as the epilogue of the movie states. The opposite was true: more and more people were giving false confessions and four women actually pled guilty to the charges. Some historians claim that this was because it became apparent that confession would save one from the noose, but there is evidence that the Court was planning to execute the confessors as well. What ended the trials was the intervention of Governor William Phips. Contrary to what Phips told the Crown in England, he was not off in Maine fighting the Indians in King William’s War through that summer, since he attended governor’s council meetings regularly that summer, which were also attended by the magistrates. But public opinion of the trials did take a turn. There were over two hundred people in prison when the general reprieve was given, but they were not released until they paid their prison fees. Neither did the tide turn when Rev. Hale’s wife was accused, as the play claims, by Abigail Williams (it was really a young woman named Mery Herrick), nor when the mother-in-law of Magistrate Jonathan Corwin was accused — although the “afflicted” did start accusing a lot more people far and wide to the point of absurdity, including various people around in other Massachusetts towns whom they had never laid eyes on, including notable people such as the famous hero Capt. John Alden (who escaped after being arrested).

-

Abigail Williams probably couldn’t have laid her hands on 31 pounds in cash in Samuel Parris’ house, to run away with John Proctor, when Parris’ annual salary was contracted at 66 pounds, only a third of which was paid in money. The rest was to be paid in foodstuffs and other supplies, but even then, he had continual disputes with the parishioners about supplying him with much-needed firewood they owed him, primarily because they were not in agreement that the parsonage should have been deeded to Parris.

-

Certain key people in the real events appear nowhere in Miller’s play: John Indian, Rev. Nicholas Noyes, Sarah Cloyce, and most notably, Cotton Mather.

-

Giles Corey was not executed for refusing to name a witness, as portrayed in the movie. The stage play is more accurate: he was accused of witchcraft, and refused to enter a plea, which held up the proceedings, since the law of the time required that the accused enter a plea and agree to be tried “before God and the country” (i.e. a jury). He was pressed to death with stones, but the method was used to try to force him to enter a plea so that his trial could proceed. Corey may have realized that if he was tried at all, he would be executed, and his children would be disinherited, but he had already deeded most of his property to his children by then anyway. (Interestingly, Miller wrote both the play and the screenplay… Who knows why he changed it to a less-accurate explanation for his punishment and execution?)

-

“The afflicted” comprised not just a group of a dozen teenage girls — there were men and adult women who were also “afflicted,” including John Indian, Ann Putnam, Sr., and Sarah Bibber — and there were more in Andover, where the total number of people accused was greater than any other town, including Salem Village.

-

There’s a tiny scene in the movie with a goat getting into someone’s garden and tempers flaring — the actual history is that three years before the witchcraft accusations, a neighbor’s pigs got into the Nurse family’s fields, and Rebecca Nurse flew off the handle yelling at him about it. Soon thereafter, the neighbor had an apparent stroke and died within a few months. This was seen as evidence in 1692 of Rebecca Nurse’s witchcraft.

-

At the end of Act II, Scene 2 in the play (p. 75), John Proctor states, “”You are pulling down heaven and raising up a whore.” In the film (Scene 74. EXT DAY. WATER’s EDGE, p. 79), John Proctor says this line, but follows it with, “I say God is dead!” This idea of the death of God dates from the 19th century work of German philosopher, Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900).

NOTE: All of the above can be verified through primary sources, which are not listed here only to avoid providing an easy on-line source of plagiarism — not that your teacher couldn’t spot a ringer like this one from a mile away. (Trust me: your teachers can usually tell when you are plagiarizing. If you think you are “getting away with it,” it may just be a temporary thing while they figure out how to prove it or catch you at it. Do your own work.) Everything stated here can be corroborated with a little research of your own, and isn’t that the point of most school assignments? Start with the the searchable on-line edition of The Salem Witchcraft Papers, Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt, the books listed in my bibliography and various rare books available on-line. I encourage you to read these for yourself!

Now I have a few questions, for anyone who is inclined to think about them or who needs an idea to start writing a paper:

-

It may not matter if one’s sole interest is in Miller work as literature or theater, but what happens when people only know history through creative works of art and not from primary sources and facts, letting someone else pick and choose between which facts to include and which to alter for their own artistic purposes and political arguments?

-

What are the current-day implications of the racial misidentification of Tituba as “black” or “African” in many high school history books and Miller’s play written in the 1950s, when all of the primary sources by the people who actually knew the real woman referred to her as “Indian”? What would happen to Miller’s story if Tituba were not portrayed as the well-worn American stereotype of a Black slave woman circa 1850 practicing voodoo, but as a Christianized Indian whose only use of magic was European white magic at the instruction of her English neighbors?

-

Since there never was a spurned lover stirring things up in Salem Village and there is no evidence from the time that Tituba practiced Caribbean Black Magic, yet these trials and executions actually still took place, how can you explain why they occurred?

-

As a result of reading Miller’s play or seeing the movie, are you more interested in what actually happened in Salem in 1692, what actually happened during McCarthyism in the 1950’s, what happens when an illicit teenage lover is spurned, or what effects infidelity has on a married couple? What is it about Miller’s work that prompts your interest in that direction?

-

Accusations of sexual-abuse against childcare providers are now sometimes referred to as “witch hunts” when the accusers are suspected of lying, as in Miller’s play, yet children’s advocates tell us that we must believe children’s claims of abuse because it certainly — horribly — does occur. How can the veracity of children’s testimony be evaluated when children have been proven to be very impressionable and eager to give the answers that adults lead them to give?

-

Why do teachers assign projects to their students to compare the events in the play to what really happened historically? What kind of conclusions do teachers expect their students to make about how to navigate between art and history when faced with the kind of information provided on this page?

Notes

1. The play premiered before anti-Communist Senator Joseph McCarthy’s actual participation started on Feb. 3, 1953. The House Committee on Unamerican Activities (HCUA), however, began their inquiries earlier than McCarthy’s participataion. Elia Kazan’s testimony before it — which is assumed to have influenced Miller — was on April 12th, 1952. Do not write to me asking about any specifics of the events in the 1950s: that’s not my area of expertise.

2. You may also want to read Robin DeRosa’s “History and the Whore: Arthur Miller’s The Crucible“, pp. 132-140 in The Making of Salem: The Witch Trials in History, Fiction and Tourism (2009).

3. It’s worth reading the entire section, pp. 335-342, for the context of this quotation. Miller describes this memory slightly differently on pages 42-43 of the same book, so it’s worth a comparison. Maybe I’ll incorporate that one into this essay at some point. © 1997, 1999, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2011 Margo Burn Return to 17th c. Index Page.

This page was last updated 06/21/13 by Margo Burns, ![]() .

.