Trees

Mark Haddon

They stand in parks and graveyards and gardens.

Some of them are taller than department stores,

yet they do not draw attention to themselves.

You will be fitting a heated towel rail one day

and see, through the louvre window,

a shoal of olive-green fish changing direction

in the air that swims above the little gardens.

Or you will wake at your aunt’s cottage,

your sleep broken by a coal train on the empty hill

as the oaks roar in the wind off the channel.

Your kindness to animals, your skill at the clarinet,

these are accidental things.

We lost this game a long way back.

Look at you. You’re reading poetry.

Outside the spring air is thick

with the seeds of their children.

A Martian Sends a Postcard Home

Craig Raine, 1979

Caxtons are mechanical birds with many wings

and some are treasured for their markings–

they cause the eyes to melt

or the body to shriek without pain.

I have never seen one fly, but

sometimes they perch on the hand.

Mist is when the sky is tired of flight

and rests its soft machine on the ground:

then the world is dim and bookish

like engravings under tissue paper.

Rain is when the earth is television.

It has the properites of making colours darker.

Model T is a room with the lock inside —

a key is turned to free the world

for movement, so quick there is a film

to watch for anything missed.

But time is tied to the wrist

or kept in a box, ticking with impatience.

In homes, a haunted apparatus sleeps,

that snores when you pick it up.

If the ghost cries, they carry it

to their lips and soothe it to sleep

with sounds. And yet, they wake it up

deliberately, by tickling with a finger.

Only the young are allowed to suffer

openly. Adults go to a punishment room

with water but nothing to eat.

They lock the door and suffer the noises

alone. No one is exempt

and everyone’s pain has a different smell.

At night, when all the colours die,

they hide in pairs

and read about themselves —

in colour, with their eyelids shut.

Do not go gentle into that good night

Dylan Thomas, 1914 – 1953

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

From The Poems of Dylan Thomas, published by New Directions. Copyright © 1952, 1953 Dylan Thomas. Copyright © 1937, 1945, 1955, 1962, 1966, 1967 the Trustees for the Copyrights of Dylan Thomas. Copyright © 1938, 1939, 1943, 1946, 1971 New Directions Publishing Corp. Used with permission.

The Lanyard by Billy Collins (Poem)

http://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/index.php?date=2008/01/26

The Lanyard

The other day I was ricocheting slowly

off the blue walls of this room,

moving as if underwater from typewriter to piano,

from bookshelf to an envelope lying on the floor,

when I found myself in the L section of the dictionary

where my eyes fell upon the word lanyard.

No cookie nibbled by a French novelist

could send one into the past more suddenly—

a past where I sat at a workbench at a camp

by a deep Adirondack lake

learning how to braid long thin plastic strips

into a lanyard, a gift for my mother.

I had never seen anyone use a lanyard

or wear one, if that’s what you did with them,

but that did not keep me from crossing

strand over strand again and again

until I had made a boxy

red and white lanyard for my mother.

She gave me life and milk from her breasts,

and I gave her a lanyard.

She nursed me in many a sick room,

lifted spoons of medicine to my lips,

laid cold face-cloths on my forehead,

and then led me out into the airy light

and taught me to walk and swim,

and I , in turn, presented her with a lanyard.

Here are thousands of meals, she said,

and here is clothing and a good education.

And here is your lanyard, I replied,

which I made with a little help from a counselor.

Here is a breathing body and a beating heart,

strong legs, bones and teeth,

and two clear eyes to read the world, she whispered,

and here, I said, is the lanyard I made at camp.

And here, I wish to say to her now,

is a smaller gift—not the worn truth

that you can never repay your mother,

but the rueful admission that when she took

the two-tone lanyard from my hand,

I was as sure as a boy could be

that this useless, worthless thing I wove

out of boredom would be enough to make us even.

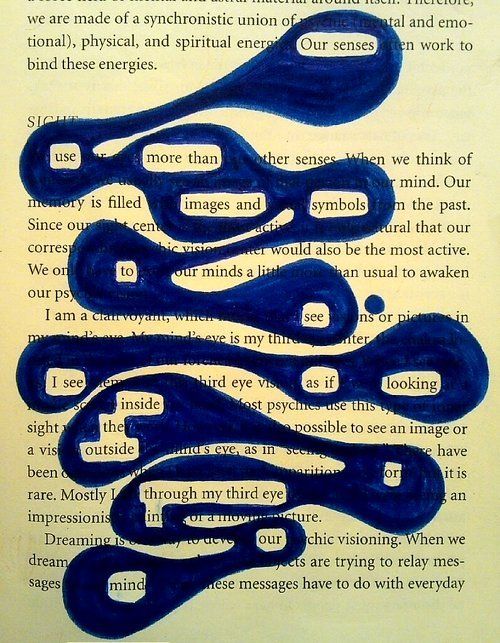

The Solipsist by Troy Jollimore (Philosophical poem)

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poem/180541

Poet’s Choice: ‘The Solipsist’ by Troy Jollimore

Sunday, August 2, 2009

A friend of mine once observed that a lot of my poems — really, a surprising number — are about the head, or the skull, or the brain. So perhaps it was inevitable that I would eventually write a poem about a solipsist: a person who thinks that he is the only person in existence and that everything else, the entire world, is just his experience, with no independent reality of its own.

I make my living teaching philosophy, but I’m always wary of putting philosophy explicitly into my poems. Randall Jarrell once warned that “poetry is a bad medium for philosophy,” and, indeed, it’s very hard to write a good poem that is also philosophically interesting. But in “The Solipsist,” I let myself try it — partly because solipsism is not a position I hold. In fact, the way the poem is supposed to work is that by the time you get to the end, you realize how utterly absurd and ridiculous the position is.

The poem began, like many of my poems, with a phrase that suggested a rhythm: In this case the first stanza grew out of the line “It’s all in your head,” and that stanza set the formal rules for the rest of the poem. The other crucial thing was a sense of the speaker, a sense of who this philosophical madman was. Once I had that . . . Poems don’t ever write themselves, really. But in the best cases, you and the poem work as partners.

The Solipsist

BY TROY JOLLIMORE

Don’t be misled:

that sea-song you hear

when the shell’s at your ear?

It’s all in your head.

That primordial tide—

the slurp and salt-slosh

of the brain’s briny wash—

is on the inside.

Truth be told, the whole place,

everything that the eye

can take in, to the sky

and beyond into space,

lives inside of your skull.

When you set your sad head

down on Procrustes’ bed,

you lay down the whole

universe. You recline

on the pillow: the cosmos

grows dim. The soft ghost

in the squishy machine,

which the world is, retires.

Someday it will expire.

Then all will go silent

and dark. For the moment,

however, the black-

ness is just temporary.

The planet you carry

will shortly swing back

from the far nether regions.

And life will continue—

but only within you.

Which raises a question

that comes up again and again,

as to why

God would make ear and eye

to face outward, not in?

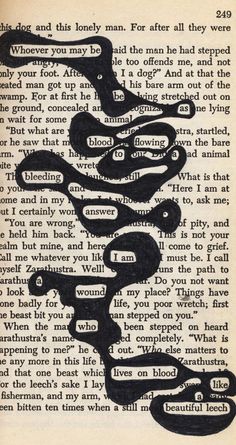

Homer by Troy Jollimore (Philosophical poem)

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poem/247152

Homer

BY TROY JOLLIMORE

Schliemann is outside, digging. He’s not

not calling a spade a spade.

The stadium where the Greeks once played

used to stand on this very spot.

Each night, Penelope, operating

in mythical time, unspools the light

gray orb Schliemann has just unearthed. Come daylight,

her hands will restitch it. The suitors sigh, waiting.

And each night I’d watch as my hero curled

himself round home plate, as if he were going

to bat for me. And I’d hold my breath, knowing

a strong enough shot might be heard round the world.

One must imagine Penelope.

One must imagine Penelope happy.

One must imagine Schliemann excavating

the dugouts and outfields of Troy, carbon-dating

the box score stats and the ticket stubs

he pulls from the lurid dirt. He rubs

the remains of Achilles’s rage on his shirt.

What does not kill you can still hurt.

Penelope’s suitors are striking out,

one after another. Their sad swings and misses.

They can’t even get to first base. She’ll cut

the stitches once more, then blow them all kisses.

Odysseus won’t care that the orb is undone.

He’ll take a swing at it with all his might.

The ball takes flight. Odysseus takes flight.

It feels to Penelope like he’s been gone

since the dawn of mankind, but he’s already zoomed

round third and flies like an arrow toward home,

as the unearthly orb trails its guts in the air —

the yarn fanning out like Penelope’s hair —

not knowing yet whether to fall foul or fair.

Source: Poetry (February 2014)

Still I Rise by Mary Angelou (Poem)

https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/still-i-rise

Still I Rise

You may write me down in history With your bitter, twisted lies, You may trod me in the very dirt But still, like dust, I’ll rise. Does my sassiness upset you? Why are you beset with gloom? ‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells Pumping in my living room. Just like moons and like suns, With the certainty of tides, Just like hopes springing high, Still I’ll rise. Did you want to see me broken? Bowed head and lowered eyes? Shoulders falling down like teardrops, Weakened by my soulful cries? Does my haughtiness offend you? Don’t you take it awful hard ‘Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines Diggin’ in my own backyard. You may shoot me with your words, You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I’ll rise. Does my sexiness upset you? Does it come as a surprise That I dance like I’ve got diamonds At the meeting of my thighs? Out of the huts of history’s shame I rise Up from a past that’s rooted in pain I rise I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide, Welling and swelling I bear in the tide. Leaving behind nights of terror and fear I rise Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear I rise Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise I rise I rise.

From And Still I Rise by Maya Angelou. Copyright © 1978 by Maya Angelou. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

Caged Bird by Mary Angelou (Poem)

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/178948

Caged Bird

BY MAYA ANGELOU

A free bird leaps

on the back of the wind

and floats downstream

till the current ends

and dips his wing

in the orange sun rays

and dares to claim the sky.

But a bird that stalks

down his narrow cage

can seldom see through

his bars of rage

his wings are clipped and

his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The free bird thinks of another breeze

and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees

and the fat worms waiting on a dawn bright lawn

and he names the sky his own

But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams

his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream

his wings are clipped and his feet are tied

so he opens his throat to sing.

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

Maya Angelou, “Caged Bird” from Shaker, Why Don’t You Sing? Copyright © 1983 by Maya Angelou. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Source: The Complete Collected Poems of Maya Angelou (Random House Inc., 1994)

Rain by Hone Tuwhare (NZ poem)

http://nzpoems.blogspot.co.nz/2011/05/rain-hone-tuwhare.html

Heaps of beautiful poems by Glenn Colquhoun!! (He is a NZ poet and a GP) (Poetry)

http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Ba25Spo-t1-body-d1.html

The first lesson

by Glenn Colquhoun

Now are you going to listen or not? There’s nothing tricky about a poem. It’s just a collection of words like one of those bunches of grapes that used to hang in the backyard, how every one had a particular shape depending on the way it grew, or like one of those macramé pot-holders Aunty Jean used to make except the words are the knots and at each one you can change direction, or like when mum cooks and some words are like mince and cheap and easy to fill you up with and contain most of what’s good for you and those are the ones she uses a lot and some words are spicy so she only uses them a little bit and like some words look so good she uses them for colour and others act differently under heat, cheese for example, to melt all through a poem which is great unless you don’t like cheese. Some bits might stick in your teeth for days unless you brush them and I know you don’t always do that. Maybe if you think of words like cars on a motorway, how if they are speeding or not being driven carefully they can easily lose control and cause an accident and then another car will hit them and then a truck and before you know it there is a huge pile-up with everyone tut-tutting, well the pile-up can be a poem too. Sometimes you’ll even find poems like grandad did with that piece of driftwood which looked like a woman with her legs crossed and if you’re lucky no one else has pinched it so you can pick it up off the ground and put your name on it and the ladies at church will wonder why on earth you have that in the garden. It can even be like when you’re laying cobblestones and every word fits neatly into the next so that sometimes there’s a pattern if you stand back far enough, or if you’re laying bricks, how you have to knock words in half to fit them into the PAGE 6end of sentences so the next layer has something to build onto and all you do all day is look at bricks and when you put your head up there’s a whole wall or a house with windows and corners that you’re surprised is there and while we’re talking about bricks sometimes you can put words together because of the way they look, brown bricks or red bricks or rough bricks or smooth bricks so people can enjoy them like when we go for a drive through Howick and mum likes the colour of the houses, and sometimes you can put them together because they hold things up and are strong and have a use even if no one sees them, bricks don’t really have a sound unless you drop them on your foot and then they make a sound that sounds like bloody hell, and sometimes when you read a poem you feel like it doesn’t even belong on the paper or that you’ve seen it before somewhere or should have seen it before or always meant to make one just like it and so if you turn around it will move behind your back, sometimes it’s like a child who makes you drop him off up the road from school so his mates won’t see you kiss him goodbye and then shoos you away as if to say ‘don’t make such a fuss’ but the way I like to think of poems the most is that they are like a lolly for your mind or an argument with a clever person who is always trying to put words into your mouth and then spends the rest of the day trying to take them back out again.

By Glenn Colquhoun

Wild Things by Alessia Cara (Lyrics)

http://genius.com/Alessia-cara-wild-things-lyrics